For two weeks, the Harvest Money pull-out offers is carrying series on the coffee value chain. This is because Uganda has hosted the G-25 Coffee Summit that brought together international stakeholders in the sector. In the first story, we look at the history and growth of the coffee value chain.

By Joshua Kato

The phrase ‘aguze emwanyi zabala’, used to be used in reference to farmers who bought new commodities after the coffee harvest started in Masaka, Kalungu and Mpigi districts in the 1960s.

“Every after a coffee season, farmers bought new items for their homes. However, the commonest reference to ‘mwanyi zabala’ was a motorcycle,” says coffee farmer Emmanuel Kibirige, the chairman of the farmers’ committee of Kammengo Organic Farmers Association (KOFA), Mpigi.

Kibirige grows coffee on over four acres. The medium-sized farmers bought motorcycles that ranged in engine capacity from the small 100cc, while others bought the powerful motorbike called BSA, a noisy 250cc bike-pronounced as ‘byese’ by the locals.

The large-scale coffee farmers bought cars and, at the time, the Volkswagen Beetle, the Morris Minor and the VW Combi were in vogue.

Although the coffee boom was affected by the Coffee Wilt Disease in the 1990s, of late, this trend is returning in greater Masaka, Mpigi and Kalungu districts, thanks to a combination of factors, including efforts by the government and Buganda Kingdom through the Mwanyi terimba campaign that have taken these areas by storm.

Katikkiro Charles Peter Mayiga started the Mwanyi Terimba campaign across Buganda about five years ago.

The campaign included encouraging farmers not only to renovate old coffee shambas, but also plant new trees.

And to cap a good cup of Ugandan coffee, through this week, Uganda is acres were under cultivation. Other than Uganda (Buganda), other countries in Africa growing the crop included Nyasaland (Malawi), Kenya and Rwanda.

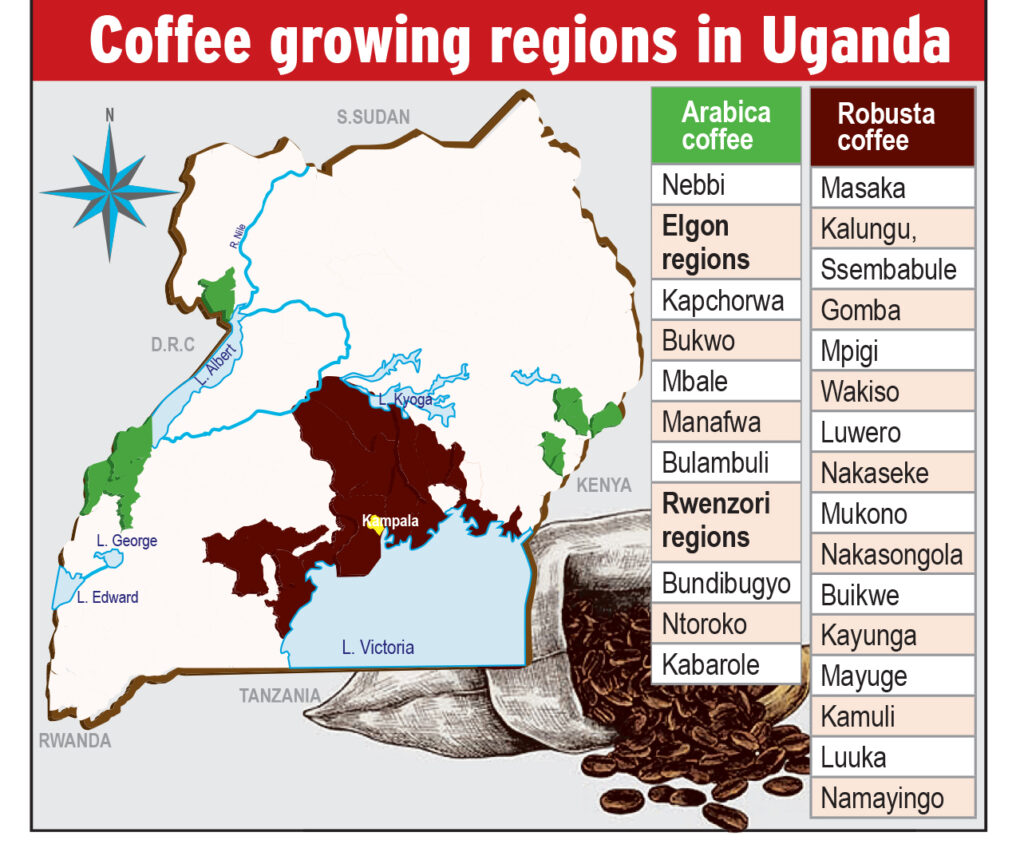

In Uganda, coffee growing was spread in the greater Masaka area, Luwero, Mubende, parts of Bushenyi, parts of West Nile, Mukono and Elgon.

“Historically, the colonial government used to enforce coffee production by using chiefs who used to inspect households to ensure compliance of production and maintenance of quality in harvesting and drying coffee beans. As a result, coffee was named kibooko (coffee grown after being caned),” Kibirige says.

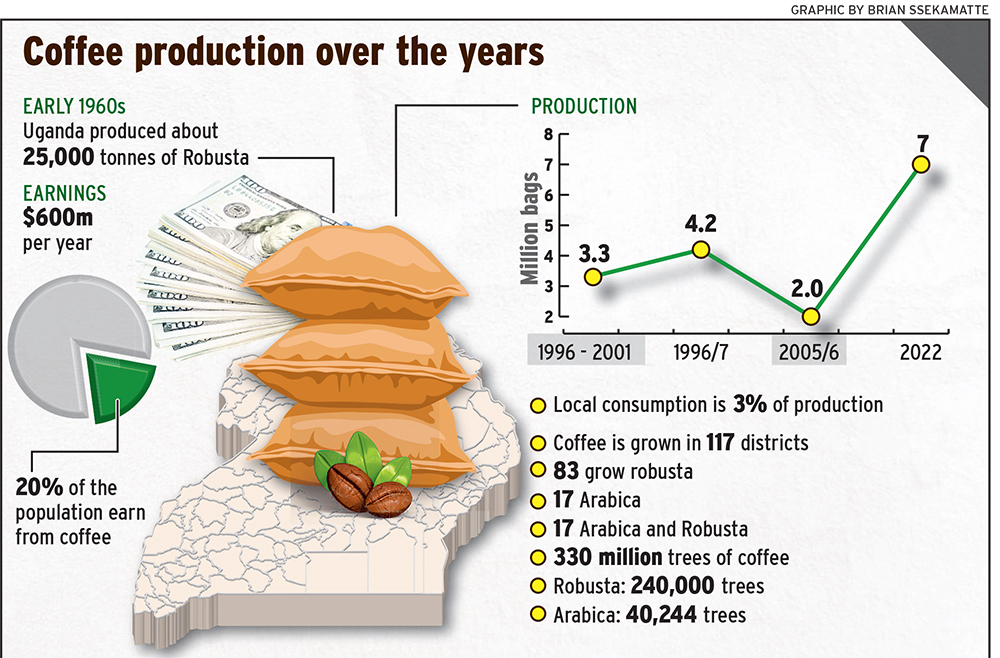

Today, coffee is grown in 117 of the country’s 146 districts. Of these, 83 of these grow only robusta, 17 districts grow only Arabica, while 17 grow both Arabica and Robusta.

“There are 330 million trees of coffee and, out of these, robusta has 240,000, while Arabica has 40,244 trees,” UCDA says.

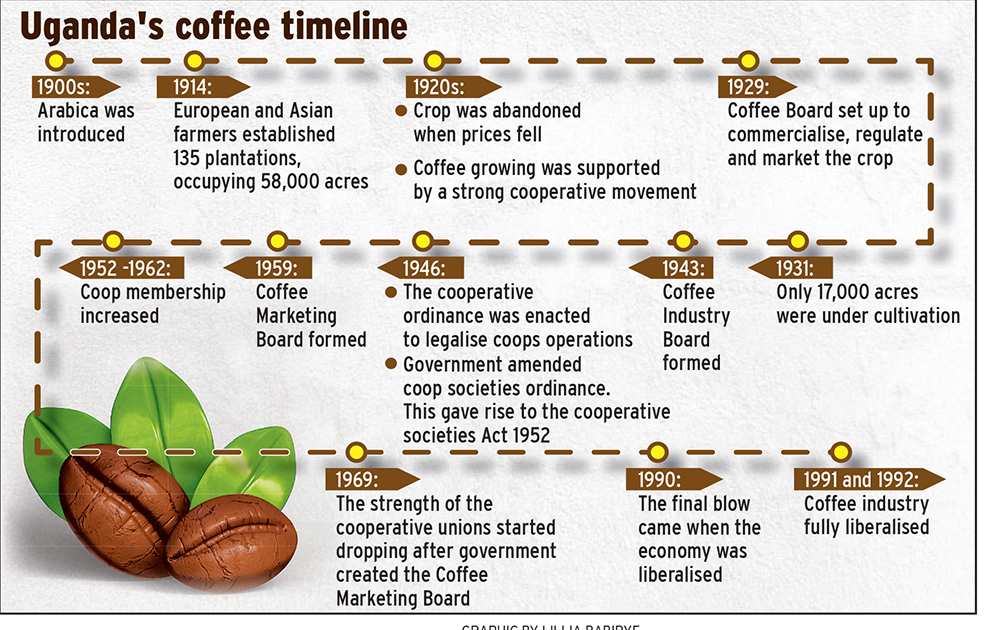

Arabica was introduced at the beginning of the 1900s, Robusta coffee is indigenous to the country, and has been a part of Ugandan life for centuries.

The variety of wild Robusta coffee still grows today in Uganda’s rainforests and is thought to be one of the rarest examples of naturally occurring coffee trees worldwide.

Most Robusta is sun-dried, although in recent years, there have been modest attempts to reintroduce wet-processing. These interventions are on-going today, under UCDA.

In the early 1960s, the Uganda coffee industry produced close to 25,000 tonnes of good quality pulped and washed Robusta, but this segment vanished entirely during the monopoly years by government, together with the plantation sector that supported it. Robusta is native to Uganda and two types are grown — ‘Nganda’ and ‘Erecta’.

An extensive clonal replanting programme combines high-yielding clones of both varieties that are vegetatively propagated. The progenies are true to type and retain their parental characteristics — they are high-yielding, mature faster and produce a bigger bean with improved characteristics.

They also tend to show resistance to Coffee Leaf Rust Disease. Coffee at a glance According to the Uganda Coffee Federation (UCF), while the economy as a whole has expanded and improved in recent years, coffee remains of vital importance, earning on average $600m per year.

It is estimated that as much as 20% of the entire population earns all or a large part its cash income from coffee. UCF explains that following decades of total state control of the sector, the coffee industry was fully liberalised between 1991 and 1992.

However, export quality control remains the responsibility of the Uganda Coffee Development Authority (UCDA), which grades and classifies all export shipments.

Production averaged almost 3.3 million bags in the six years from 1996 to 2001, with a peak of 4.2 million bags in 1996/7 (a total last seen in 1972) and a low of 2.0 million in 2005/6.

Then, to about seven million bags in 2022. The proportion of Arabica coffee fluctuates from around eight to 10% of the total. Local consumption is limited at around 3% of production.

Cooperatives spurred coffee growth Masaka is largely the grandfather of coffee growing in Uganda. The region was selected as one of the very first commercial coffee growing areas in the early 20s.

The environment, so near Lake Victoria and the fertile soils contributed to this choice. The locals did not disappoint. They planted coffee depending on the size of their land holdings.

Some planted as many as 20 acres. Such was the strength of coffee that towns like Masaka were developed by individuals using earnings from coffee. In the 60s and 70s, what is now ‘Greater Masaka’ was the ‘mecca’ of coffee farming in the country.

This area included Masaka, Kalungu, Kyotera, Ssembabule, Rakai, Bukomansimbi and Lwengo districts.

At the time, Ssebatta Musisi, now in his 70s, was a young man, studying at St Henry’s College, Kitovu and later St Mary’s College, Kisubi.

His father paid fees using earnings from coffee. Although Ssebatta’s farm is in Lwengo district, he still prides himself in having witnessed the growth of Masaka city, thanks to coffee.

Coffee growing was supported by a very strong co-operative movement that started around the end of the 1920s. Among these included Masaka Union, which catered for farmers in greater Masaka area, Banyankore Kweterana for western Uganda, West, West Mengo Growers etc.

Co-operatives in Uganda can be traced in Mubende district, where in 1913 four farmers decided to market their crop collectively. They became known as The Kinakulya Growers.

They co-operated as a result of a response to the poor coffee and other product prices that Asian produce buyers gave to peasant farmers.

“In 1920, five groups of farmers in Mengo met in Kampala to form the Buganda Growers Association, whose supreme goal was to control the domestic and export marketing of members’ produce,” says Fred Ahimbisibwe, who worked with the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Cooperatives.

Counterparts in other parts of the country shared this vision and acted accordingly. A co-operative movement was thus born to fight the exploitative forces of the colonial administrators and alien commercial interests which monopolised domestic and export marketing.

On the other hand, the colonialists and the coffee buyers did not like the emergence of the organised groups.

“They considered the emergence of co-operatives as subversive. Laws were enacted to make it an offence for any financial institution to lend money to any African farmer,” Ahimbisibwe says.

Because of these restrictions, co-operatives operated underground until 1946 when the co-operative ordinance was enacted to legalise their operations.

Peasant farmers saw the 1946 ordinance to increase government control in their business and many groups refused to register under it. Among others, the ordinance called upon them to register their names and be monitored by the government.

“It was not the function of government to guide private enterprise, as doing so would arouse suspicion. The co-operative movement would be stronger if it was independent of government. It was a legitimate and reasonable aspiration of co-operative societies to be free of government control because it is not always good for government to influence the management of co-operatives,” Ahimbisibwe says.

In light of the above pointer, government amended cooperative societies ordinance 1946. This gave rise to the cooperative societies Act 1952, which was accommodative and provided the frame work for rapid economic development.

It provided enough autonomy to make registration acceptable to the cooperative groups that had defied the 1946 ordinance. It also provided for both the elimination of discriminatory price policies and offered private African access to coffee processing.

“Between 1952 and 1962, cooperative membership increased. The cooperative district unions acquired considerable importance,” Ahimbisibwe says.

Groups like West-Mengo, Masaka Union, Banyankore Kweterana, etc, gained prominence as their membership grew. By 1962, there were seven coffee curing works in the hands of cooperative unions. Many people were employed and cooperative unions became the most notable institutions in the districts.

“It was a privilege working for the cooperatives. They paid well and had a good understanding of the market,” says Alex Musisi, who worked under cooperatives across the central region from the 1970s up to 1994.

The co-operatives had storage facilities for their members’ produce. They had trucks to transport produce from the villages to these storage facilities.

They had constant linkages with markets across the world, which enabled them sell produce easily.

“Some of these, like Banyankore Kweterana, gained so much wealth that they had over 50 trailers transporting produce. They had their own processing facilities too,” says Moses Magambo, who worked as a clerk at Banyankore Kweterana in the 1970s.

Coffee farmers were assured of a market for their product under the co-operative systems.

“The co-operative supported the farmer with inputs and, at harvest, a farmer simply delivered the produce to the nearest store,” Kibirige says. Sometimes, farmers were paid promptly, while other times they were given promissory notes which they could even take to schools to guarantee their children’s school fees.

According to Patrick Lubega, who worked at the International Food Policy Research Institute, the strength of the cooperative unions started dropping in 1969 after government created the Coffee Marketing Board (CMB) and similar cash crop commodity bodies.

“Previously, the co-operatives had been selling their produce directly to the markets in Europe. However, the creation of CMB meant that they now had to sell the produce through the body. CMB operated as an intermediary between the co-operatives and the external markets. The price of key commodities like coffee was now set by CMB,” Lubega said.

This obviously reduced their profit levels. Before they could recover from this development, political turmoil started cutting through the country.

For example, Banyankore Kweterana lost a lot of property, including their main processing plant at Kakoba in Mbarara during the 1979 war. It was hit and destroyed by bombs during the fighting in Mbarara. Then between 1982 and1985, the same cooperative lost trucks and coffee stocks.

“It was common for both government and rebel soldiers to commandeer trucks belonging to cooperatives to carry fighters into the war zones. Many of these trucks were never returned,” says Magambo.

In 1983, CMB was also grossly mismanaged as senior army officers took control over it. But the final blow came in 1990 when the economy was liberalised.

“The liberalisation of the economy made doing coffee business more competitive for the co-operatives that had largely thrived as commodity monopolies,” Lubega says.

With business opened up, hundreds of private buyers registered to buy coffee, for example. Before the liberalisation, a group like Bugisu Cooperative Union collected around 10,000 tonnes of coffee alone.

However, by 1994, soon after liberalisation, they collected just 2,000 tonnes. In recent years, new coffee co-operatives have emerged, including Kibinge Coffee Farmers Cooperative Society, Gumutindo Coffee Cooperative and Ankole Coffee Producers Cooperative.

Old groups like Masaka Union, Sebei Union and Banyankore Kweterana are also being revived to further enhance the coffee trade.